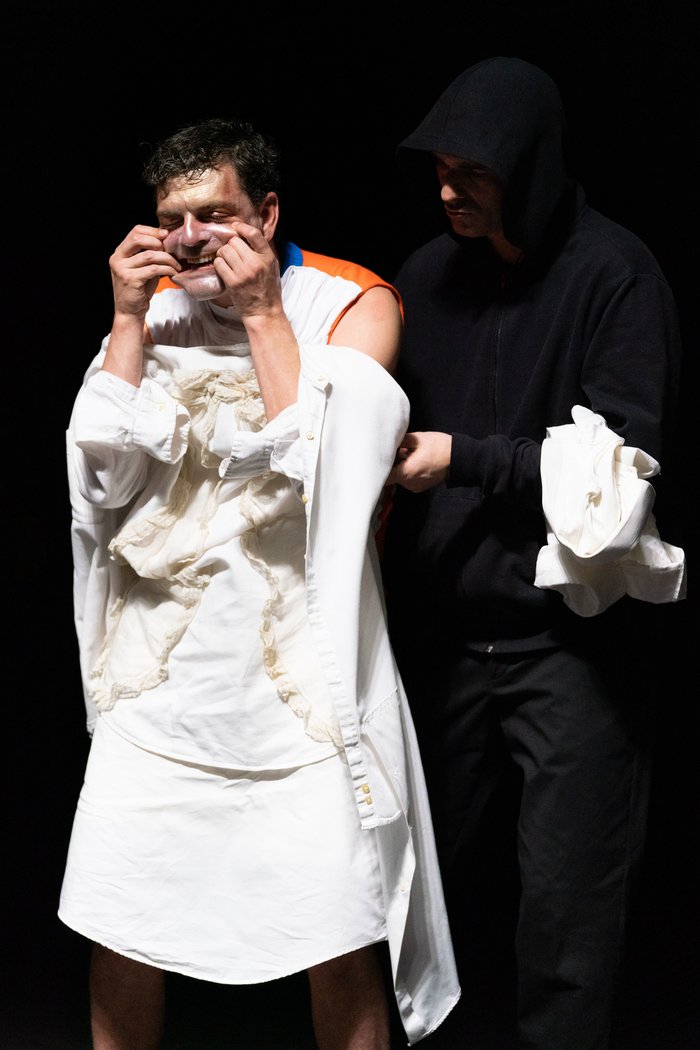

In a continuation of the “MONUMENT” series, the choreographer Eszter Salamon connects traces of Sicilian musical archives, mummification rituals of the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo and historical references to the Sicilian revolution of 1848. “HETEROCHRONY / Palermo 1599–1920” – a HAU co-production – imagines a continuum between life and death, the cohabitation of the living and the dead. The scheduled performances on April 8 and 9 at HAU had to be cancelled due to the corona virus. Read an interview by Bojana Cvejić, first published by PACT Zollverein – where the play premiered.

What does Monument 0.6 commemorate? What’s behind the title “Heterochrony: Palermo 1599-1920”?

I began thinking about the question of how death is included in life when I visited the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo. From 1599, the monks of the Capuchin order have observed a peculiar custom: instead of burying their dead, they mummified them in this place, which is still open for visit. Later on, the custom spread to include wealthy citizens who paid to have the body of their loved ones preserved. In 1920, the last body joined a collection of about 1250 mummies. Since the modern times, death has been evacuated from our societies; the dead disappear from our view, their bodies are removed from the perception of the living. The encounter with the mummies of the Catacombs brought about a kinaesthetic shock for me. Getting so close to the appearance of the dead body I recalled the massive deaths of our times, genocide, carnage, but also sick bodies and illnesses like AIDS and cancer our society tends to hide and marginalize.

What does it mean to make a “monument” for you? This one is the sixth in a series.

The concept of “monument” is a bit of a bluff or a provocation. It is an exaggerated manner of naming power in the processes of memory and the writing of history. Who is the subject of history, who remembers and what is to be remembered. “Monument” means for me taking time to reflect on the past.